THE ORANGE NAVY – PART 3

The U-Boats Strike

Following the British victory at the Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914, morale in the Royal Navy was high and that in the German Imperial Navy correspondingly low. To a degree, this was to remain the same throughout the remainder of the war. There was, however, one arm of the German Navy that was eager to strike at its British enemies and that was the U-Boat arm.

HMS Pathfinder, 5th September 1914

HMS Pathfinder was a cruiser, commissioned in 1905. At the start of the First World War she was based at Rosyth as part of the 8th Destroyer Flotilla. On the morning of 5th September 1914 Pathfinder was patrolling the Firth of Forth accompanied by destroyers of the 8th Flotilla in a SSE direction. At some point the destroyers turned away and headed back north, but Pathfinder carried on. It has been alleged that she was making only 5 knots to conserve coal.

At 15.30 hours she was spotted by the German submarine U-21, which had been in the Firth of Forth for some time. U-21 was under the command of Kapitänleutnant Otto Hersing, who decided to launch a torpedo attack. At 15.43 he fired one Type G 50cm torpedo. At 15.45 lookouts on the Pathfinder saw the torpedo approaching and evasive action was taken, but at 15.50 the torpedo struck the cruiser on the starboard side beneath the bridge.

The resulting explosion was so severe that it seems the magazine blew up. The wreck of the Pathfinder has been explored and it looks as though everything before the first funnel disintegrated. Captain Martin-Peake realised that the ship would go down very quickly and ordered the stern gun to be fired to attract the attention of vessels nearby. The explosion must have damaged the gun’s mounting as, after firing a single round, the gun toppled from its mounting and slid over the stern, taking the gun crew with it. The stern rose to a sixty degree angle, the bow sheared off, and Pathfinder slipped beneath the waves. There was no time to launch boats.

First on the scene were fishing boats from Eyemouth, who saw the full measure of the devastation caused by the explosion. The writer Aldous Huxley, then just a young man of twenty, was staying at nearby St Abbs and saw the explosion. He mentioned it in a letter to his father, -

I dare say Julian told you that we actually saw the Pathfinder explosion — a great white cloud with its foot in sea.

The St. Abbs' lifeboat came in with the most appalling accounts of the scene. There was not a piece of wood, they said, big enough to float a man—and over acres the sea was covered with fragments—human and otherwise. They brought back a sailor's cap with half a man's head inside it. The explosion must have been frightful.

The destroyers HMS Stag and HMS Express headed for the pall of smoke where the Pathfinder had been. One of them developed an engine problem when a water inlet was blocked by a human leg.

2

Casualty figures are difficult to establish with certainty. There seems to have been a crew of 268, of whom only 18 survived.

Chief Petty Officer Telegraphist R H Newman

One of those who were lost with the ship was a brother Orangeman, Chief Petty Officer Telegraphist Richard H Newman, 183585. Brother Newman was the son of Richard and Mary Newman of 3 Trevor Road, Southsea. He was 35 years of age and a member of Sons of William Loyal Orange Lodge 652, which met in Gillingham. His name appears on Panel 3 of the Chatham Naval Memorial.

The U-Boats Strike

Following the British victory at the Heligoland Bight on 28th August 1914, morale in the Royal Navy was high and that in the German Imperial Navy correspondingly low. To a degree, this was to remain the same throughout the remainder of the war. There was, however, one arm of the German Navy that was eager to strike at its British enemies and that was the U-Boat arm.

HMS Pathfinder, 5th September 1914

HMS Pathfinder was a cruiser, commissioned in 1905. At the start of the First World War she was based at Rosyth as part of the 8th Destroyer Flotilla. On the morning of 5th September 1914 Pathfinder was patrolling the Firth of Forth accompanied by destroyers of the 8th Flotilla in a SSE direction. At some point the destroyers turned away and headed back north, but Pathfinder carried on. It has been alleged that she was making only 5 knots to conserve coal.

At 15.30 hours she was spotted by the German submarine U-21, which had been in the Firth of Forth for some time. U-21 was under the command of Kapitänleutnant Otto Hersing, who decided to launch a torpedo attack. At 15.43 he fired one Type G 50cm torpedo. At 15.45 lookouts on the Pathfinder saw the torpedo approaching and evasive action was taken, but at 15.50 the torpedo struck the cruiser on the starboard side beneath the bridge.

The resulting explosion was so severe that it seems the magazine blew up. The wreck of the Pathfinder has been explored and it looks as though everything before the first funnel disintegrated. Captain Martin-Peake realised that the ship would go down very quickly and ordered the stern gun to be fired to attract the attention of vessels nearby. The explosion must have damaged the gun’s mounting as, after firing a single round, the gun toppled from its mounting and slid over the stern, taking the gun crew with it. The stern rose to a sixty degree angle, the bow sheared off, and Pathfinder slipped beneath the waves. There was no time to launch boats.

First on the scene were fishing boats from Eyemouth, who saw the full measure of the devastation caused by the explosion. The writer Aldous Huxley, then just a young man of twenty, was staying at nearby St Abbs and saw the explosion. He mentioned it in a letter to his father, -

I dare say Julian told you that we actually saw the Pathfinder explosion — a great white cloud with its foot in sea.

The St. Abbs' lifeboat came in with the most appalling accounts of the scene. There was not a piece of wood, they said, big enough to float a man—and over acres the sea was covered with fragments—human and otherwise. They brought back a sailor's cap with half a man's head inside it. The explosion must have been frightful.

The destroyers HMS Stag and HMS Express headed for the pall of smoke where the Pathfinder had been. One of them developed an engine problem when a water inlet was blocked by a human leg.

2

Casualty figures are difficult to establish with certainty. There seems to have been a crew of 268, of whom only 18 survived.

Chief Petty Officer Telegraphist R H Newman

One of those who were lost with the ship was a brother Orangeman, Chief Petty Officer Telegraphist Richard H Newman, 183585. Brother Newman was the son of Richard and Mary Newman of 3 Trevor Road, Southsea. He was 35 years of age and a member of Sons of William Loyal Orange Lodge 652, which met in Gillingham. His name appears on Panel 3 of the Chatham Naval Memorial.

3

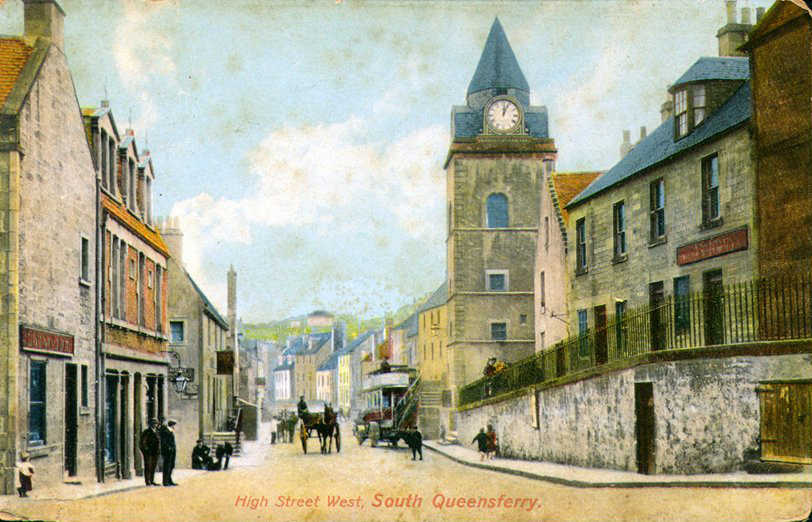

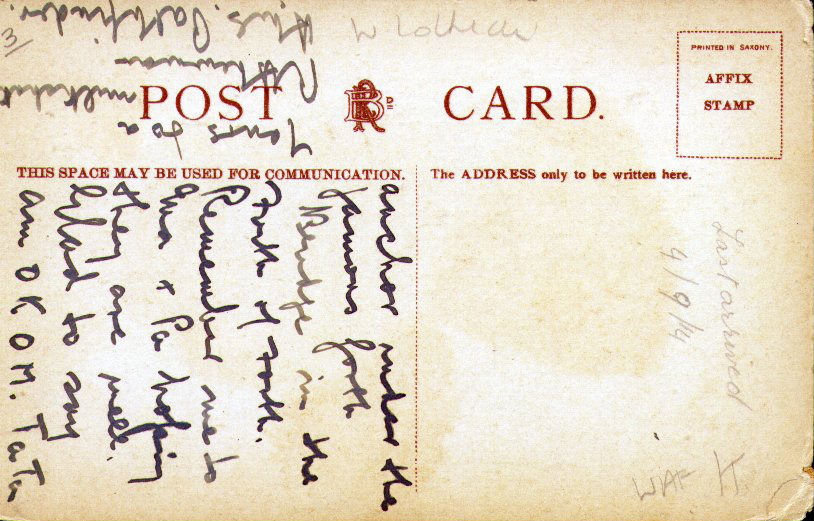

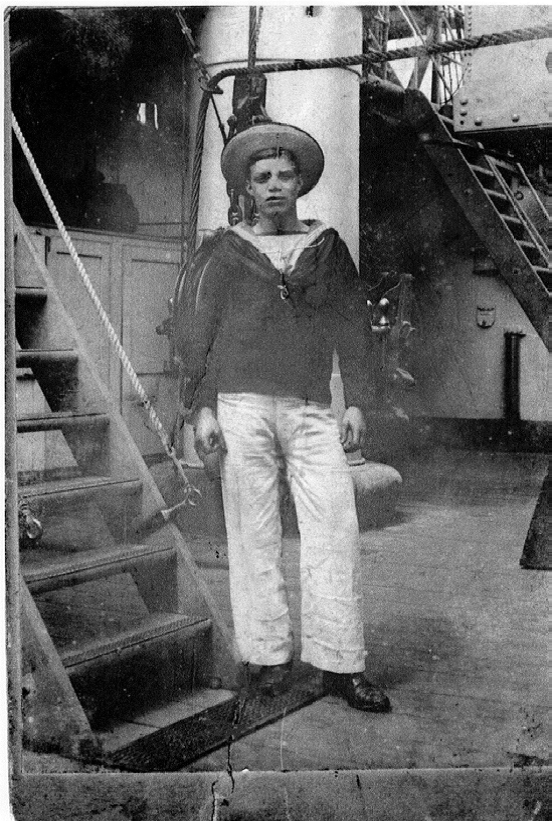

The illustrations shown here are of a Post Card sent by Brother Newman to his family shortly before he set out on his last voyage – “Remember me to Ma and Pa hoping they are well. Glad to say am OK, Ta Ta.” I have been able to include it by the goodwill of the owner, Mr J Boner of the South Queensferry History Group, and Mr Frank Hay, also of the Queensferry History Group.

Three ships down – 22nd September 1914

The “Cressy” class of armoured cruisers were six ships built for the Royal Navy between 1899 and 1901. They were the Cressy; the Sutlej; the Aboukir; the Hogue; the Bacchante; and the Euryalus. By 1914 they had mostly been overtaken by technical developments in warship construction and had been placed in reserve. On the outbreak of war they were brought out of reserve and all but the Sutlej became the 7th Cruiser Squadron.

The ships of the 7th Cruiser Squadron were manned largely by transferees from other ships and from the Royal Naval Reserve. They were assigned the task of patrolling a part of the southern North Sea called “the broad fourteens”, as part of the defence of the English Channel against any German incursions. The Squadron had been held in reserve during the Battle of the Heligoland Bight as possible reinforcements, but they had not been needed. Commodore Roger Keyes and Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt, the architects of the victory at the Heligoland Bight, became concerned that the ships were much too vulnerable to attack. Although notionally capable of a speed of 21 knots they were now capable of only 15 or even 12 knots. Keyes and Tyrwhitt passed their concerns on to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, and the First Sea Lord Prince Louis of Battenberg. They agreed and directed that the Squadron should be withdrawn. This was blocked by Vice-Admiral Frederick Sturdee, Chief of War Staff at the Admiralty, who objected that, obsolescent as they were, there were no ships to replace them. A compromise was reached whereby the Squadron would retain its patrolling duties until newer ships, which were almost ready, could take their place.

On the morning of 22nd September 1914, the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy were on patrol. They were making about 10 knots and were not zigzagging, but they had lookouts posted. Euryalus had returned to port the previous day for refuelling and accompanying destroyers had also returned to port. The weather was quite calm. At 06.00 the ships were sighted by the U-9, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen. At 6.20 Weddigen fired a single torpedo at the nearest ship, which was the Aboukir, and the ship was hit on the starboard side. The engine room flooded and the ship came to a stop in the water. The Aboukir was commanded by Captain Drummond, who was the senior officer in the patrol. No submarines had been sighted, so Drummond assumed that the Aboukir had hit a mine and ordered the other two ships up to help. After twenty-five minutes the Aboukir capsized and sank.

Weddigen next fired two torpedoes at the Hogue. The U-9 was now seen by the British crews and the Hogue fired a shell at the U-9 which dived to avoid British counter-measures. The two torpedoes then struck the Hogue whose Captain gave orders to abandon ship. After ten minutes the Hogue capsized and sank. This was at 07.15.

The Cressy was aware that a German submarine was in the area but stayed to pick up survivors. The U-9, however, was not finished and fired its remaining torpedoes at the

4

surviving cruiser. The ship was struck by the torpedoes, capsized, and floated upside down for a while. There were now survivors in the water from three sunken British cruisers.

A Dutch steamship, the Flora, another steamship, the Titan, and two Lowestoft trawlers, the Coriander and the JGC, came to take men out of the water and British destroyers arrived at 10.45. By that time the U-9 had submerged and was lying low to escape attention. From the three sunken cruisers the losses were 62 officers and 1,397 men.

Weddigen escaped back to Germany and went on to sink more ships. He received most of Imperial Germany’s highest decorations but was killed on 18th March 1915 when his submarine (he was commanding U-29 by then) was sunk by HMS Dreadnought.

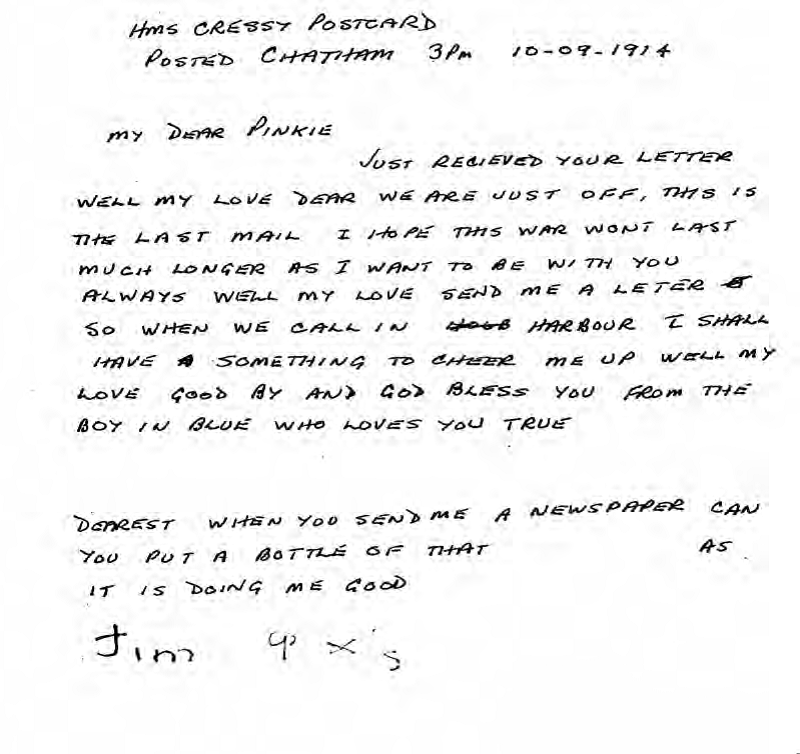

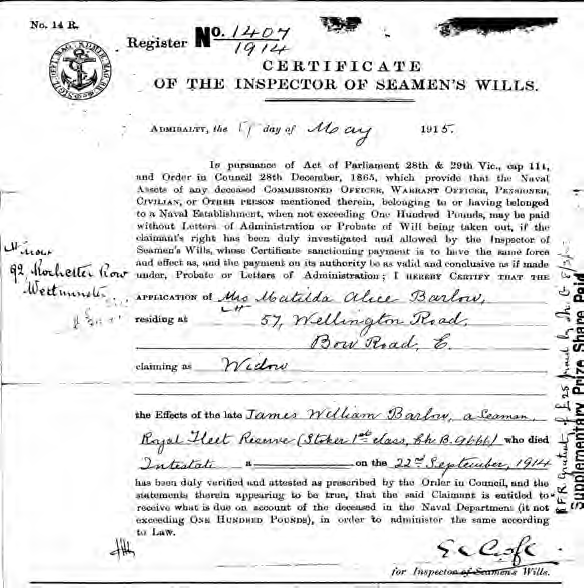

Stoker James W Barlow

The Roll of Honour contained in the Grand Orange Lodge of England’s Report Book for 1915 has three names of brethren serving on HMS Cressy. Two of these are Brothers W Metcalfe and W McCabry. Their names do not appear in the crew list for those who were on board on 22nd September 1914. It is possible that their details were forwarded for the Roll of Honour and afterwards they were posted elsewhere.

The third member named in the Roll of Honour as being aboard HMS Cressy is Stoker James W Barlow, and he is recorded as having lost his life during the submarine attacks on 2nd September 1914. James William Barlow is recorded on Panel 4 of the Chatham Naval Memorial where is shown to have been a Stoker First Class with the Service Number SS/107176.

We now know rather more about Brother Barlow because of a web site set up to commemorate the crews of the three cruisers. The web site is the work of a Dutch gentleman, Mr Hendrik van der Linden. He calls the web site “The Live Bait Squadron”, as that was the name given to the 7th Cruiser Squadron because of the inadvisability of having such dangerously exposed ships on patrol. Those wishing to visit the web site should go to –

http://www.livebaitsqn-soc.info/

Mr van der Linden was contacted by the granddaughter of Brother Barlow who offered much information. The contact was Mrs Dana Mary Cressy Brown and she supplied the following information -

Mrs Dana Brown tells us,

“I am Dana Mary Cressy, and my mother was Cressy Alice Barlow. She was born December 1914, so never knew her dad. I have Admiralty letters to my Grandmother (Matilda, Alice nee Phillips), notifying her of Jim’s death plus other memorabilia and research that I have done at the Public Record Office in Kew. JWB’s ancestors were mostly watermen/lightermen on the river Thames in London. I am 80 plus. Bless you for all of your interest and writing a book which I sadly will not be able to read unless it comes out in audio version. I was able to read ‘Three before Breakfast’ before I lost my sight and I am glad the interest in ‘Live Bait’ is still continuing.’

5

Later on she writes:

‘James was aged 26 years when he died. He only had one child, a daughter named Cressy Alice, born three months after he died, my mother. She had me and my brother Ted (Edward Andrew Morley).

I have three children, Linda, David and Carl. All born U.S. Citizens as their father was in the US Navy.

My mother Mathilda ‘Alice’ Barlow nee Phillips was a ‘cashier’ in the Hyde Park Kiosk, who put herself through Pitman’s Shorthand and Typing School and came out with very fast ‘speeds’. She worked all her life as a Secretary even into the 80’s. She decided to die on 11 November 1991 ‘because it is a very sad day’ after she lost her hearing and sight. Her brother Edward also had been killed in WW1 in France. She was aged 101 years.

I have a photo of James and also the last postcard of the Cressy which he sent. The pencil writing is very faint, but my husband is deciphering it.

Best wishes on this sad day of Commemoration and Remembrance. Dana”

(e-mail sent 22 September 2013).

The illustrations shown here are of a Post Card sent by Brother Newman to his family shortly before he set out on his last voyage – “Remember me to Ma and Pa hoping they are well. Glad to say am OK, Ta Ta.” I have been able to include it by the goodwill of the owner, Mr J Boner of the South Queensferry History Group, and Mr Frank Hay, also of the Queensferry History Group.

Three ships down – 22nd September 1914

The “Cressy” class of armoured cruisers were six ships built for the Royal Navy between 1899 and 1901. They were the Cressy; the Sutlej; the Aboukir; the Hogue; the Bacchante; and the Euryalus. By 1914 they had mostly been overtaken by technical developments in warship construction and had been placed in reserve. On the outbreak of war they were brought out of reserve and all but the Sutlej became the 7th Cruiser Squadron.

The ships of the 7th Cruiser Squadron were manned largely by transferees from other ships and from the Royal Naval Reserve. They were assigned the task of patrolling a part of the southern North Sea called “the broad fourteens”, as part of the defence of the English Channel against any German incursions. The Squadron had been held in reserve during the Battle of the Heligoland Bight as possible reinforcements, but they had not been needed. Commodore Roger Keyes and Commodore Reginald Tyrwhitt, the architects of the victory at the Heligoland Bight, became concerned that the ships were much too vulnerable to attack. Although notionally capable of a speed of 21 knots they were now capable of only 15 or even 12 knots. Keyes and Tyrwhitt passed their concerns on to the First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, and the First Sea Lord Prince Louis of Battenberg. They agreed and directed that the Squadron should be withdrawn. This was blocked by Vice-Admiral Frederick Sturdee, Chief of War Staff at the Admiralty, who objected that, obsolescent as they were, there were no ships to replace them. A compromise was reached whereby the Squadron would retain its patrolling duties until newer ships, which were almost ready, could take their place.

On the morning of 22nd September 1914, the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy were on patrol. They were making about 10 knots and were not zigzagging, but they had lookouts posted. Euryalus had returned to port the previous day for refuelling and accompanying destroyers had also returned to port. The weather was quite calm. At 06.00 the ships were sighted by the U-9, under the command of Kapitänleutnant Otto Weddigen. At 6.20 Weddigen fired a single torpedo at the nearest ship, which was the Aboukir, and the ship was hit on the starboard side. The engine room flooded and the ship came to a stop in the water. The Aboukir was commanded by Captain Drummond, who was the senior officer in the patrol. No submarines had been sighted, so Drummond assumed that the Aboukir had hit a mine and ordered the other two ships up to help. After twenty-five minutes the Aboukir capsized and sank.

Weddigen next fired two torpedoes at the Hogue. The U-9 was now seen by the British crews and the Hogue fired a shell at the U-9 which dived to avoid British counter-measures. The two torpedoes then struck the Hogue whose Captain gave orders to abandon ship. After ten minutes the Hogue capsized and sank. This was at 07.15.

The Cressy was aware that a German submarine was in the area but stayed to pick up survivors. The U-9, however, was not finished and fired its remaining torpedoes at the

4

surviving cruiser. The ship was struck by the torpedoes, capsized, and floated upside down for a while. There were now survivors in the water from three sunken British cruisers.

A Dutch steamship, the Flora, another steamship, the Titan, and two Lowestoft trawlers, the Coriander and the JGC, came to take men out of the water and British destroyers arrived at 10.45. By that time the U-9 had submerged and was lying low to escape attention. From the three sunken cruisers the losses were 62 officers and 1,397 men.

Weddigen escaped back to Germany and went on to sink more ships. He received most of Imperial Germany’s highest decorations but was killed on 18th March 1915 when his submarine (he was commanding U-29 by then) was sunk by HMS Dreadnought.

Stoker James W Barlow

The Roll of Honour contained in the Grand Orange Lodge of England’s Report Book for 1915 has three names of brethren serving on HMS Cressy. Two of these are Brothers W Metcalfe and W McCabry. Their names do not appear in the crew list for those who were on board on 22nd September 1914. It is possible that their details were forwarded for the Roll of Honour and afterwards they were posted elsewhere.

The third member named in the Roll of Honour as being aboard HMS Cressy is Stoker James W Barlow, and he is recorded as having lost his life during the submarine attacks on 2nd September 1914. James William Barlow is recorded on Panel 4 of the Chatham Naval Memorial where is shown to have been a Stoker First Class with the Service Number SS/107176.

We now know rather more about Brother Barlow because of a web site set up to commemorate the crews of the three cruisers. The web site is the work of a Dutch gentleman, Mr Hendrik van der Linden. He calls the web site “The Live Bait Squadron”, as that was the name given to the 7th Cruiser Squadron because of the inadvisability of having such dangerously exposed ships on patrol. Those wishing to visit the web site should go to –

http://www.livebaitsqn-soc.info/

Mr van der Linden was contacted by the granddaughter of Brother Barlow who offered much information. The contact was Mrs Dana Mary Cressy Brown and she supplied the following information -

Mrs Dana Brown tells us,

“I am Dana Mary Cressy, and my mother was Cressy Alice Barlow. She was born December 1914, so never knew her dad. I have Admiralty letters to my Grandmother (Matilda, Alice nee Phillips), notifying her of Jim’s death plus other memorabilia and research that I have done at the Public Record Office in Kew. JWB’s ancestors were mostly watermen/lightermen on the river Thames in London. I am 80 plus. Bless you for all of your interest and writing a book which I sadly will not be able to read unless it comes out in audio version. I was able to read ‘Three before Breakfast’ before I lost my sight and I am glad the interest in ‘Live Bait’ is still continuing.’

5

Later on she writes:

‘James was aged 26 years when he died. He only had one child, a daughter named Cressy Alice, born three months after he died, my mother. She had me and my brother Ted (Edward Andrew Morley).

I have three children, Linda, David and Carl. All born U.S. Citizens as their father was in the US Navy.

My mother Mathilda ‘Alice’ Barlow nee Phillips was a ‘cashier’ in the Hyde Park Kiosk, who put herself through Pitman’s Shorthand and Typing School and came out with very fast ‘speeds’. She worked all her life as a Secretary even into the 80’s. She decided to die on 11 November 1991 ‘because it is a very sad day’ after she lost her hearing and sight. Her brother Edward also had been killed in WW1 in France. She was aged 101 years.

I have a photo of James and also the last postcard of the Cressy which he sent. The pencil writing is very faint, but my husband is deciphering it.

Best wishes on this sad day of Commemoration and Remembrance. Dana”

(e-mail sent 22 September 2013).

6

7

Like Brother Newman who went down with HMS Pathfinder, all three of the brethren on the Roll of Honour who are shown as serving on the Cressy were members of Sons of William Loyal Orange Lodge 652, which met at that time at the Foresters’ Hall on King Street in Gillingham, Kent. The precise membership of the Lodge is not known but it must have been large. The Roll of Honour has the names of 112 members of this lodge alone, and of those only five were in the Army while 107 were in the Royal Navy.

Loyal Orange Lodge 652 was founded in 1888 and originally met in Woolwich. In 1893 the Lodge moved to Chatham but by 1907 the Lodge had moved to Gillingham. The Lodge ceased to send in returns sometime in the 1920’s, but it was revived in 2008 and has thrived since then.

Gillingham had an Orange Lodge previous to 652, which was Loyal Orange Lodge 448. This Lodge had originally met in Old Brompton but had moved to Gillingham in 1885. When there it met at a hostelry called the Ghuznee Fort Tavern on Fox Street. Although the Lodge went defunct before the First World War had broken out the name of the Tavern reflects a military connection. In 1839, during the First Afghan War, the British attacked a great fort, the Ghuznee, which was captured when the main gate was blown up by Sappers. There was a School of Military Engineering near the Tavern, which took its name after the action as a tribute to the Sappers when they returned home from the campaign.

On the website www.kenthistoryforum.co.uk there was a lively discussion about the pub during 2012. A Mr David Pott made very interesting contributions as his great grandfather, Mr Frederick Pott, had been landlord between 1894 and his death in 1906. This was just after LOL 448 moved to the Masonic Hall in Anglesea Hill in Woolwich. Mr Pott tells us that his great grandfather was a Mason and the Masons used to meet in the function room of the pub. The pub still exists but its name was changed to The Countryman some time ago.

HMS Audacious, 27th October 1914

The British were now aware that, although they maintained a superiority in surface ships, new weapons like the submarine might erode that superiority over time. Beside the submarine, the mine also presented such a threat and, on 27th October 1914, HMS Audacious, a King George V-class battleship which had been launched only two years before, struck a mine off the north coast of Ireland. At first it was thought to be a torpedo that had struck the ship and the rest of the Squadron sailed away, following procedure adopted since the sinking of the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy. Audacious was stabilised by counter-flooding and was still able to make headway so her Captain thought to beach her. Most of the ship’s crew were taken off and, during the afternoon, it became clear that the damage had been caused by a mine and not by a torpedo. The pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Exmouth was ordered out to take Audacious under tow. It became obvious, however, that the ship was floundering and the remaining crewmen were ordered off at 19.15. Around 20.45 Audacious capsized and floated upside down until 21.00 when the ship blew up. The explosion was so great that a member of the crew of HMS Liverpool, 800 yards away, was killed by falling debris. The Exmouth had arrived by this time but had been unable to do anything to save the Audacious.

The Orange interest in this episode lies in the fact that three brethren were known to have been on board the Exmouth at this time. They were Brother W H Garnsworthy, of Ulster Scot

8

Loyal Orange Lodge 287 based at Devonport, and Brothers H Fisher and L W Dyer, both of whom were members of Excelsior Loyal Orange Lodge 56 based at Plymouth.

Michael Phelan

Historian

Grand Orange Lodge of England

30th June 2014

Like Brother Newman who went down with HMS Pathfinder, all three of the brethren on the Roll of Honour who are shown as serving on the Cressy were members of Sons of William Loyal Orange Lodge 652, which met at that time at the Foresters’ Hall on King Street in Gillingham, Kent. The precise membership of the Lodge is not known but it must have been large. The Roll of Honour has the names of 112 members of this lodge alone, and of those only five were in the Army while 107 were in the Royal Navy.

Loyal Orange Lodge 652 was founded in 1888 and originally met in Woolwich. In 1893 the Lodge moved to Chatham but by 1907 the Lodge had moved to Gillingham. The Lodge ceased to send in returns sometime in the 1920’s, but it was revived in 2008 and has thrived since then.

Gillingham had an Orange Lodge previous to 652, which was Loyal Orange Lodge 448. This Lodge had originally met in Old Brompton but had moved to Gillingham in 1885. When there it met at a hostelry called the Ghuznee Fort Tavern on Fox Street. Although the Lodge went defunct before the First World War had broken out the name of the Tavern reflects a military connection. In 1839, during the First Afghan War, the British attacked a great fort, the Ghuznee, which was captured when the main gate was blown up by Sappers. There was a School of Military Engineering near the Tavern, which took its name after the action as a tribute to the Sappers when they returned home from the campaign.

On the website www.kenthistoryforum.co.uk there was a lively discussion about the pub during 2012. A Mr David Pott made very interesting contributions as his great grandfather, Mr Frederick Pott, had been landlord between 1894 and his death in 1906. This was just after LOL 448 moved to the Masonic Hall in Anglesea Hill in Woolwich. Mr Pott tells us that his great grandfather was a Mason and the Masons used to meet in the function room of the pub. The pub still exists but its name was changed to The Countryman some time ago.

HMS Audacious, 27th October 1914

The British were now aware that, although they maintained a superiority in surface ships, new weapons like the submarine might erode that superiority over time. Beside the submarine, the mine also presented such a threat and, on 27th October 1914, HMS Audacious, a King George V-class battleship which had been launched only two years before, struck a mine off the north coast of Ireland. At first it was thought to be a torpedo that had struck the ship and the rest of the Squadron sailed away, following procedure adopted since the sinking of the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy. Audacious was stabilised by counter-flooding and was still able to make headway so her Captain thought to beach her. Most of the ship’s crew were taken off and, during the afternoon, it became clear that the damage had been caused by a mine and not by a torpedo. The pre-dreadnought battleship HMS Exmouth was ordered out to take Audacious under tow. It became obvious, however, that the ship was floundering and the remaining crewmen were ordered off at 19.15. Around 20.45 Audacious capsized and floated upside down until 21.00 when the ship blew up. The explosion was so great that a member of the crew of HMS Liverpool, 800 yards away, was killed by falling debris. The Exmouth had arrived by this time but had been unable to do anything to save the Audacious.

The Orange interest in this episode lies in the fact that three brethren were known to have been on board the Exmouth at this time. They were Brother W H Garnsworthy, of Ulster Scot

8

Loyal Orange Lodge 287 based at Devonport, and Brothers H Fisher and L W Dyer, both of whom were members of Excelsior Loyal Orange Lodge 56 based at Plymouth.

Michael Phelan

Historian

Grand Orange Lodge of England

30th June 2014